Wow, guys. Now THIS was a pleasant surprise. What was advertised as some B-list action thriller turned out to be - thanks to mesmerizing cinematography, outstanding performances from the entire cast, a killer story, a propulsive euro-synthpop soundtrack and striking art-house direction from Bronson's Nicolas Refn - hands-down the best movie of the year. If you haven't, now is the time to go out and see it. If you're reading this odds are you have time to kill. Also lots of spoilers, so there's that.

Drive at first seems to defy classification; it blends genres and styles as diverse as splatter, chase, crime drama and neo-noir with 60s antiheroes, David Lynch send-ups and 80s burnout aesthetics. The result is highly stylized, existentialist thrill ride...but trust me, it's a lot less pretentious than I'm making it sound! Anyway, what surprised me most about the movie - and this is something many people have picked up on - was the one genre that cohesively united all of Drive's disparate elements; it's totally a superhero film. It doesn't look like a superhero film at first (it hardly plays out like the dime-a-dozen origin stories on the screen these days) but if The Dark Knight showed us there could be a movie about a superhero that wasn't a superhero movie, this film has now proven the opposite. This is a superhero movie that is not about a superhero...or, more accurately, not about a superhero we instantly recognize as such. Refn, for his part, has commented extensively on the genre's influence on Drive. QUOTE BOMB:

"...Drive was essentially an allegory of a superhero in the making. He became a superhero at the end of the movie and that's why it's a happy ending...In the beginning, he is there for her as a human being and when she needs him as a hero, he's there as a hero. He is what you need him to be. It's why he will continue to roam the landscape being a driver of the night, the superhero with a scorpion sign on his back as he protects the innocents against injustice."

"By day, he was a human being, by night he was a hero. And the movie is about his transformation into this superhero, by bringing his human morals into the hero role, so that he does what he does for the right reasons."

"You can kind of say that the Driver is a man who is caught between two worlds. At night, he is a man in costume who roams the streets of L.A., wanting to protect the innocent. And in the day, he's a car mechanic and a stuntman. And through the course of the movie, he realizes he's schizophrenic in a sense that he doesn't have two personalities, but he's two people. And he, through the course of the movie, becomes the superhero that he plays in films, and saves the innocents against the evil … it's mythological storytelling, which is what superhero stories are."

Riding (OR SHOULD I SAY DRIVING HURHURRR) on Refn and Ryan Gosling's words, I want to take a closer look at how the aesthetics, symbols and conventions of the superhero genre have informed Drive. For starters, our protagonist is referred to only as the "Driver," a superhero-esque codename relating to his persona and abilities; the alias wouldn't feel out of place among one of the X-Men. Like all the great superheroes, the Driver is very much an archetype - he's that same antihero stock character as the Man With No Name or Frank Bullitt or any of the samurai Toshiro Mifune played, you've seen him in various media dozens of times before. Of course the Driver's a bit of a deconstruction of that trope too - his stoicism, rather than making him seem tougher, primarily softens him, his unassuming toothpick a stark contrast Clint Eastwood's gruff cigarillo. But this still plays into the superhero dynamic, because when in the last 25 years have superheroes not been all about deconstruction?

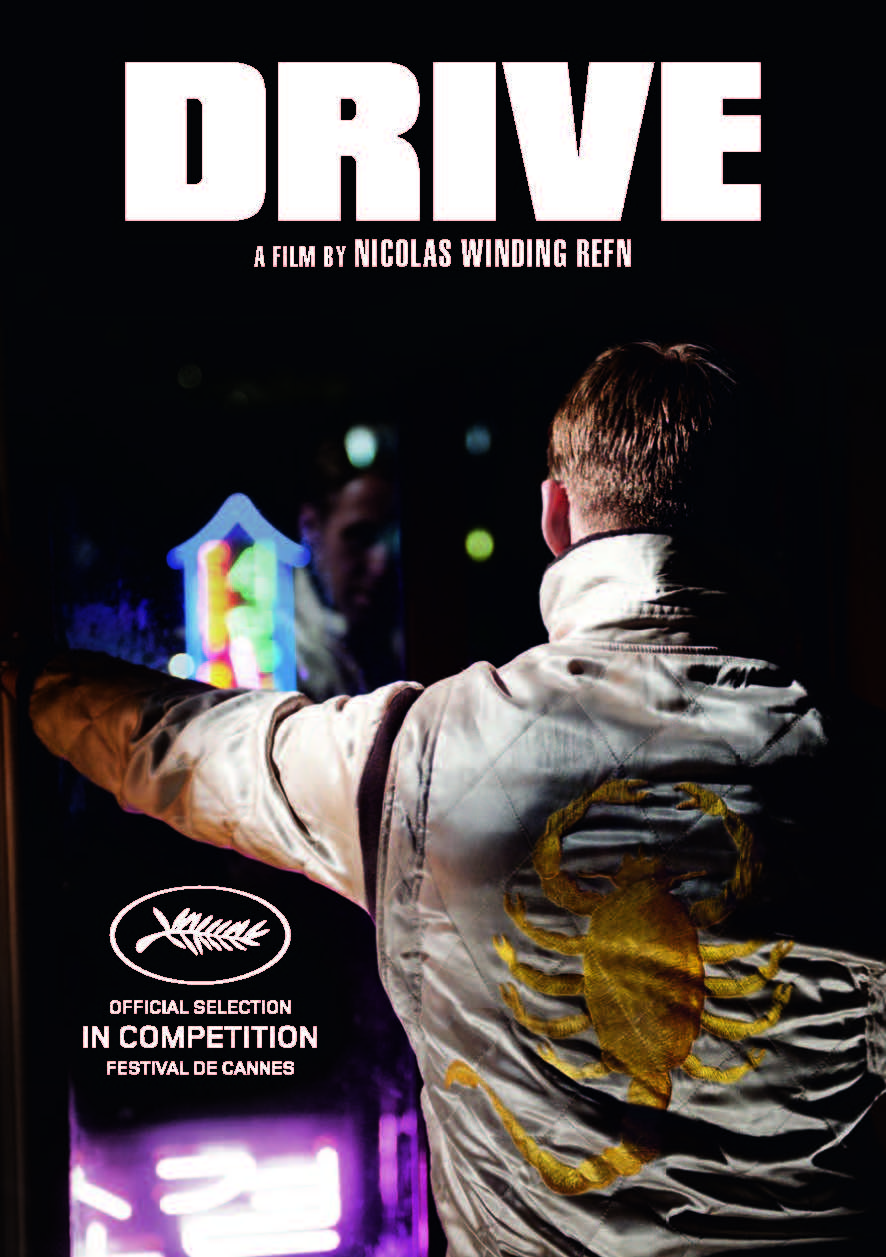

By day, the enigmatic Driver is a stunt...uhh, driver for Hollywood action films. Meta right? It's like this was written by Grant Morrison or something. By night, though, he's a wheelman-for-hire, the best at what he does (sound familiar?). But when innocent people - his neighbor/love interest Irene and her young son Benicio - are put in danger by the mob, the Driver abandons this selfish use of his skills and becomes a superhero (also sound familiar?), striking against organized crime from the darkness with impeccable combat prowess (also also sound familiar?). What most soundly cements the superhero analogy is the fact that he dons a costume during his nighttime exploits: a white satin jacket with a gold scorpion embroidered on the back. It may be more subtle than the capes and tights we're used to, but it is still quite clearly a superhero costume as it is utterly unique, it is worn solely when he asserts his extraordinary abilities and, most importantly, it invokes an animal totem.

Historically, animal totems have played an enormous role in the creation of superhero identities. Bruce Wayne was inspired to take on the archetypal qualities of a bat in what is perhaps the most iconic origin story. Peter Parker famously had the characteristics of a spider thrust upon him, and the best Spidey stories in recent memory have meditated on the totemic nature of Spider-Man's world and of superhero

comics in general. Like these heroes and so many others, the Driver is conscious of his emblem, and when he puts on his jacket he takes up the mantle of the scorpion. It hearkens back to that cornerstone of all great superheroes and superhero stories, mythology. Specifically, the fable of the scorpion and the frog, which the Driver paraphrases to his archenemy. And here's where things get deeeeeeeeeeep...

You know the story. Scorpion needs to make it over the river so he tries to hitch a ride on top of a frog. Frog is afraid scorpion will sting him. Scorpion explains that if he did that they would both drown. So frog ferries scorpion along and wouldn't you know it, just before they reach land scorpion stings him in the back, dooming them both. Frog asks why scorpion would pull that shit, to which scorpion responds, "that is my nature." The question of human nature is what Drive is all about: are individuals predisposed to behave by a certain irreversible nature? Are they predisposed to conflicting drives struggling for dominance? Are they able to transcend or change their nature? Can they transform or elevate themselves by embracing their drives? Are people capable of understanding or recognizing what they even are? Can we be a real human being and a real hero? It's a regular Jodorowsky, this one.

There's a great scene that perfectly sums up the question Drive poses. The Driver and Benicio are watching a cartoon together early in the film, and Driver asks the boy if a shark in the cartoon is the bad guy. Benicio says yes. "How can you tell he’s the bad guy?," Driver asks. "He’s a shark," the boy casually rationalizes. The Driver inquires, "Are all sharks bad?" and the young child nods his head. The scene could easily be (read: IS) referring to a number of characters in the movie, the most obvious being the Driver himself. It's also referencing Benicio's father, whom the audience is predisposed to hate until he actually appears onscreen and turns out to be a great person thrown into awful, inescapable circumstances. And to Driver's mentor (his Alfred, if you will), Shannon, another good guy who makes a bad choice that leads to disastrous consequences. Perhaps even to the antagonist Bernie Rose, a ruthless mobster who seems to genuinely regret the measures he must take to protect himself. Are any of these people intrinsically good or bad? Are any of them conscious of their individual human natures, if they even exist? Are their actions and behavior, their drives, determined by innate, instinctive characteristics? At first glance the Driver seems to serve as a profound 'YES' to these questions, but that's the beauty behind his lack of backstory and dialogue. We have no idea what he's thinking or feeling or how his environment may have shaped him; he's a total mystery to us. He's Rorschach without the caption boxes telling us his thoughts.

Compelling stuff, no?

Believe it or not, this digression I've taken ties in perfectly to the superhero stuff I'm supposed to be talking about. But first we have to take one last detour. Remember at the end of Batman Begins, when Bruce and Rachel are

talking at the ruins of Wayne Manor? Rachel feels up Bruce's face (if

I'm remembering the scene correctly) and declares "This is your mask.

Your real face is the one that criminals now fear. The man I loved, the

man who vanished...he never came back at all." Well all that is

obviously a load of bullshit; it's not a simple dichotomy between Bruce and Batman. Batman is clearly not his true persona, just as

his actual voice isn't a constipated chain smoker's. The Batman

identity is just as much a mask as millionaire playboy Bruce is, and although Rachel may think otherwise for some ill-defined reason, that is not the personality she is addressing right now. The

real person behind these facades, the man you loved and you think

vanished, is the one you're fucking talking face-to-face to you dumb

bitch: the highly disciplined, driven, perceptive, introspective,

resourceful and self-reliant Bruce Wayne. The man who has devoted his

life to a higher ideal and uses "Batman" as a tool to realize it.

Alright, now to get back on track. We're at the final lap, folks! To finish his transformation, the Driver dons a mask to hide his identity near the end of his origin story, completing his superhero costume. Crucially, the mask is taken from his day job, when the Driver needed to look like one of the actors for a car crash scene. It belongs in the realm of secret identity, not superhero. Drive knows better than Rachel, you see; it recognizes that a man's identity, his true nature, is much more nebulous than any clear-cut duality, especially between hero and secret identity. The entities are not so clearly defined - far from it - nor are they completely separate from one another. Perhaps there are elements of both in one another. Perhaps one morphs into the other. If human nature is an unanswerable question, than any attempts to explain it by ghettoizing its aspects into two definitive, opposite camps will ring as false as Rachel's half-baked analysis.

It's funny how similar the ending of Drive is to that of The Dark Knight; both have the protagonist speeding off into the darkness, with the screen cutting to black. The difference is that the ending to The Dark Knight is ominous, because by the picture's end Batman is not supposed to be a hero, while the ending of Drive is hopeful for the opposite reason. We started out with a man without any drive and saw him self-actualize. We saw him fall in love, transcend and become a real hero.

If Drive is any indication, we may soon be seeing a comparable transformation in the superhero film genre. I was once afraid that in the near future the superhero flick would over-saturate the market and go the way of the Western, that the genre would devour itself as people flocked away from the same formulaic origin stories over and over again. We saw a hint of that this summer: Thor, X-Men: First Class and Captain America all did very, very well at the box office (not so much Green Lantern), but they nevertheless failed to meet studio expectations by a great deal. There was no Iron Man among this crop of new franchises, and the only one to come even somewhat close was the first released. In light of seeing the formula applied with such ingenuity and unconventionality in Drive, I'm now confident that the superhero movie will not just survive, but will thrive in ways we have now only begun to see as it is freed from the constraints that once bound it. Yeah, the superhero movie will be fine.

It's just the superhero comic book movies that are gonna be fucked.

No comments:

Post a Comment